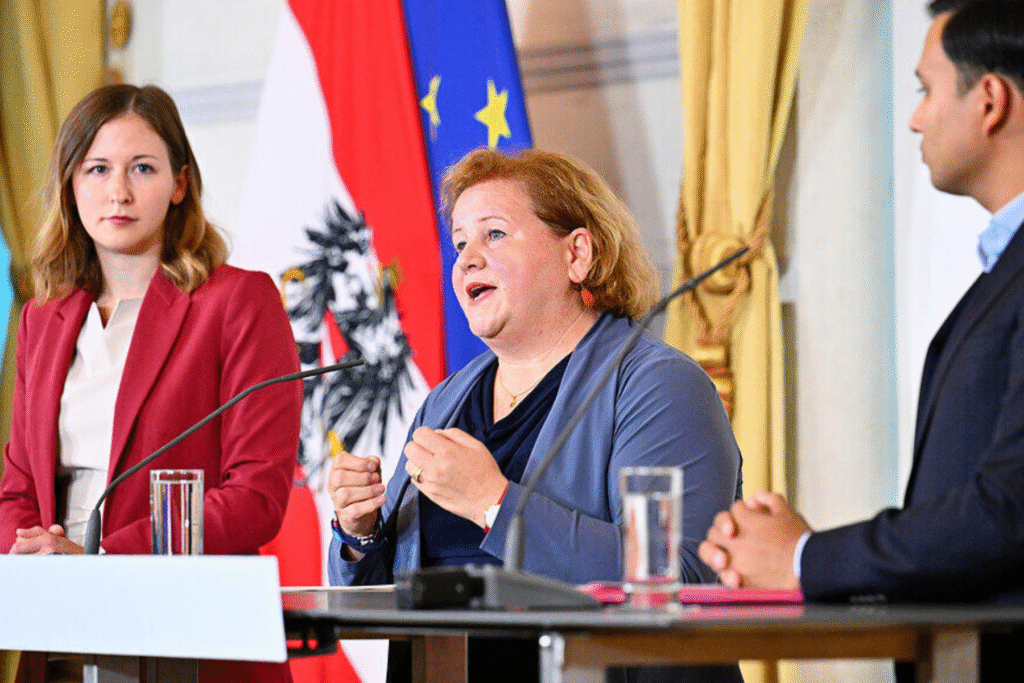

The federal government on Monday gave the “starting signal” for the “New Social Assistance” program announced in the government program. Social Minister Korinna Schumann (SPÖ), Integration Minister Claudia Plakolm (ÖVP), and NEOS parliamentary group leader Yannick Shetty presented the main points of the planned reform. The proposal remains fairly vague, but its focus is on nationwide standardization, an integration phase, and children. The reform is set to come into force in 2027.

The government’s plans for the “New Social Assistance” program were already outlined in the government program. The key message at Tuesday afternoon’s press conference in the Federal Chancellery was that negotiations with the states are now starting. “We are here to say: It’s starting,” said Schumann when asked what was new compared to previously circulated plans.

Implementation will take time. The goal is to have the reform in place by early 2027. “This is truly a major reform, something that cannot be achieved overnight,” said Schumann. “Now begins the hard work of finding a common path and a joint solution. I am very hopeful that there will be a good outcome.” A Council of Ministers report is expected to be adopted this week, with an “initial meeting” scheduled for Thursday, September 25, with state representatives and social policy spokespersons.

At that meeting, the government will also present the constitutional service’s legal opinion regarding constitutional and jurisdictional issues connected with the reform. The report has been available for ten days, but its content will first be shared with the states before further steps are announced, Schumann said.

The reform envisions nationwide standardization of currently state-specific regulations, along with previously announced oversight of employable recipients by the Public Employment Service (AMS). “We need to get away from the patchwork system,” said Schumann. Social benefits are intended to be “needs-based, integration-oriented, and future-oriented” and a “springboard into self-sufficiency,” according to government materials. At the same time, the principle of fairness in relation to employment income must be maintained. Schumann emphasized the need to focus on those unable to participate in the labor market due to age or disability.

Integration Phase As Central Point

A mandatory integration program “from day one” is planned. This will focus on learning German, job placement, and values training—along with sanctions (such as benefit cuts) for non-compliance. During this “integration phase,” benefits will be lower than the full amount—described as “integration assistance.”

Integration Minister Plakolm clarified that this integration phase will not apply to Austrian citizens. Last week, the Social Ministry had suggested it might apply to all, causing confusion among coalition partners ÖVP and NEOS.

NEOS leader Shetty called the plan a “true mammoth project, a huge reform.” “This is the starting signal for a system change in social assistance,” which should become more unified, fair, and precise.

The reform also foresees measures to combat child poverty and improve “equal opportunities” for all children and adolescents—a long-standing SPÖ demand under the term “child basic security.” It is now referred to as “future security for children.” According to Schumann, the goal is to give children “opportunities and chances” through transfer payments but with a “strong focus on in-kind benefits,” such as childcare facilities, early education, after-school and holiday care, and “a healthy meal in an educational facility.” Child healthcare is also to be improved.

Plakolm: Social Assistance Must Be “Fair”

Integration Minister Plakolm stressed that social assistance must be “fair and unambiguous.” She noted that billions had already been spent on social assistance and minimum benefits—“far too often on people who have not paid a cent into the system and view benefits as a comfortable substitute for employment.” Social assistance must be “clearly temporary and the last safety net.”

She argued that working families must always have significantly more than those on benefits, referring to recurring debates about very high payments to large families—for example, a Syrian family reportedly receiving €6,000 in social assistance and €3,000 in family benefits. “Such examples show that the system has completely lost balance,” Plakolm said.

She also stated that the legal service had confirmed it would be constitutional to count family benefits toward social assistance. “All child-related costs should be covered by social assistance, so there is no need to add another €3,000,” Plakolm argued. For migrants, she stressed, social benefits would only be available after three years, and full integration benefits only if all requirements were met.

Shetty emphasized Austria’s tradition of solidarity but said there would be “no backing for those who deliberately block integration.” He also called for a “fast track” to the labor market for recognized asylum seekers so they could “start paying taxes instead of costing taxes.” He noted, however, that the €9,000 family case was an “extreme example,” adding that this showed why in-kind benefits were the right approach.

Schumann added that enforceability was key when it came to sanctions, as this would help improve integration into the labor market, something she said was particularly important to her as labor minister.

A key government objective is to redefine child benefit rates under social assistance. Currently, these vary by state. The 2019 Social Assistance Principles Act originally set maximum rates for children, with a staggered scale: 25 percent of the compensatory allowance for the first child, 15 percent for the second, and 5 percent for each additional child. The Constitutional Court struck this down in December 2019, ruling it discriminatory toward larger families and therefore unconstitutional. As a result, child benefit rates are now set by each state without federal guidelines.

FPÖ Calls It A “Deceptive Package,” Greens See “Nothing New”

Criticism came from the FPÖ. Social spokesperson Dagmar Belakowitsch called it “pure window dressing and a dangerous deceptive package.” Instead of “finally stopping immigration into the welfare system,” the government was creating “a new magnet for welfare tourism.” She said the focus was not on restricting access but rather on integrating asylum seekers, and called the promised “mandatory integration from day one” a “smokescreen.”

The Greens were also dissatisfied, but for different reasons. Labor and social spokesperson Markus Koza said: “Once again little that is concrete and nothing new—just recycled program points.” He urged the government to “sit down with social organizations and design a comprehensive reform that truly deserves the name,” calling for minimum instead of maximum child rates and a separate child basic security outside social assistance.

Caritas President Nora Tödtling-Musenbichler welcomed the start of the process but warned against cuts. No one should fall below subsistence levels, she said. What is needed are subsistence-level minimum rates and the combined planning of social assistance and child basic security.